Fixing the housing crisis together

Jez Sweetland, PROJECT Director, Housing Festival

This blog is pulled from the script of Jez’s recent TEDX Bristol talk, which will be released in 2024. Find out more about TEDX Bristol.

What is a home to you? Just a roof over your head, a place of shelter? Of course, it’s so much more… a home provides a sense of connection to place and of belonging. For many of us its foundational in how we live - essential for our sense of human dignity. Most of us would agree having a secure, quality and safe home is a core basic human need without which the very notion of life and dignity is massively eroded if not destroyed. And yet for thousands in this country, that basic dignity – that basic human right is denied. In England we now have 104, 000 households living in Temporary Accommodation (TA) costing the taxpayer £1.7bn a year, a 100% increase since 2016.

The uncomfortable reality is for many of us – the housing crisis is good news. Since the housing market is built on scarcity of supply, if you’re lucky enough to be a homeowner you’re having a very good housing crisis – in the sense that the value of home your home has increased.

Five years ago, I set up the Bristol Housing Festival as a ‘think and do tank’ – committed to acting as a catalyst to enable change and innovation in housing. We’ve explored the fundamental question – ‘why is it so hard to build the homes we need to overcome the crisis we are in?’ and we’re optimistic that there is a solution - one you can be part of and one that is good news for everyone.

Surprisingly, The barrier to solving the housing crisis isn’t lack of land or money. Whilst it is true that we’re not building enough homes, the real issue is that we’re also not focusing on building the right kind of homes. We desperately need to focus on building more social housing with genuinely affordable rent – known as social rent housing or council housing.

You maybe thinking ‘but we are already building too many homes’ – because you’ve heard the government target was 300 000 homes a year, but here are some stats to challenge that:

In 1980 we built over 90,000 social rent homes –homes, in 2020 we built just 7,500.

The average number of homes built over the last ten years is about 178,000 homes, somewhat short of the quoted 300,000 target.

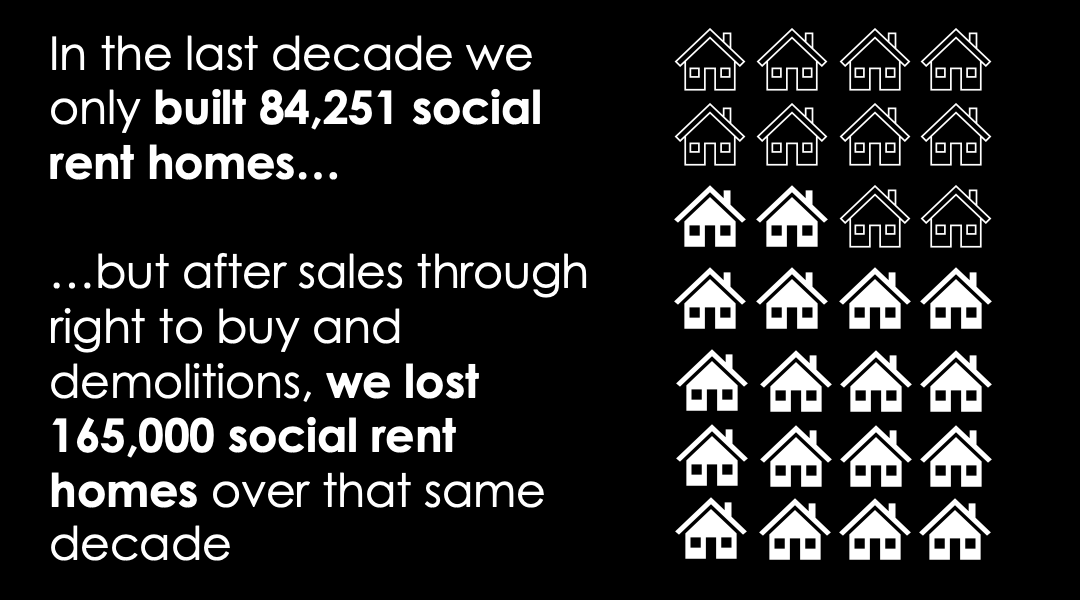

Over the last decade, we’ve ‘lost’ more social rent homes than we’ve built, leading to a net deficit (see the below slide) which has significantly exacerbated the TA crisis.

We can keep building homes but if they’re not built in the right way, in the right places, for the right people, we risk building more investments but not addressing our actual housing needs.

Part of the problem is that within the current model, the UK’s housing system is driven by profit (viability). We have one primary supply chain of housebuilders, and major housebuilders are experts in maximising land value through successful planning applications. In this model, limiting supply is one of the key levers to control risk and protect profit. To be clear, I’m not seeking to demonize any of the UK’s major housebuilders - we need them. But it is increasingly foolish to recognise a desperate and growing social housing need without addressing the limitation of the UK’s primary supply chain in how we build homes.

Because we only have one primary supply chain, we have ended up with a ‘structural deficit’ in housing supply, and only by solving this deficit can we meet the needs of the most vulnerable in our society. In my view, we can then also address wider affordability issues (and start to address how the next generation will afford to buy or rent their own homes). But we must build our system back up layer by layer for the benefit of all.

How we got here

To understand how we got here we must address a key element of housing provision – the interplay of the housing market and housing provision for the most vulnerable in society.

Unitary and Local Authorities have a legal obligation to provide accommodation for households with priority needs who present as homeless. This is known as Temporary Accommodation (TA). We now have 1,300 households in TA in Bristol and over 100,000 in the UK.

The problem is the State traditionally provided sufficient funding to build and provide genuinely affordable social rent housing (rent that could be paid by Housing Benefit) but since the 80’s when we pulled the plug out of the bath tub (right to buy) and turned off the taps (effectively reducing housing subsidy levels to make social housing less costly to the public purse) we simply don’t have enough social rent homes. As a result, we now heavily rely on the private rental sector to meet that legal obligation to provide TA. Placements that were intended to be for weeks now run for months, if not years, as there is not enough genuinely affordable housing. As the cost of private rent has increased (forcing more people into housing insecurity) Bristol City Council now loses over £12m a year in subsidy loss – the difference it pays out to private landlords for securing accommodation vs what it receives from government in housing benefit. In effect we have created an ever worsening human and economic emergency.

According to research commissioned by Crisis and Shelter, we need to build an additional 90,000 social rent homes a year to meet the country’s need. Essentially, a more focussed ‘build, build, build’ rhetoric, but with a relentless focus to build the right homes to address that structural deficit, tackle social injustice and address the most broken element of the housing crisis.

How we build dignity back into our housing system

First – build homes in a new way.

There is an opportunity for the public sector to incubate a new supply chain of factory manufactured housing (MMC: Modern Methods of Construction). These homes can be delivered and accelerated at pace and operate to a different economic model to the UK’s major housebuilders. This model is not primarily based on land acquisition and creating value through a successful planning application. Instead, they make their profit on the actual build of the home. Incubating this supply chain will speed up the delivery of houses and build zero carbon housing, helping us build at scale in a way that is kind to people and the planet.

Second – identify unlikely land.

Many local authorities have hundreds of unused land plots in their ownership including former garage sites, car parks and old industrial land. These brown- and greyfield sites tend to be a problem in the current model because they’re hard to get planning permission for or make profit on (They’re not viable). However, Local Authorities have an opportunity to unlock this land by working on them as a collective and focussing on a new economic model of viability that looks to the full societal value of the housing as social infrastructure and not just the cost of building. For example, we know that the cost of poor quality or insufficient housing to the NHS is £1.4bn a year – but we don’t currently consider the potential cost savings or the wider societal benefits in the viability of homes on these sites. Arguably, these smaller sites are also better for social integration as they allow for small developments that are not overwhelming to existing communities and can help us protect crucial green space. Bristol City Council and others are testing this now. See our Climate Smart Cities Challenge or Enabling Housing Innovation for Inclusive Growth project pages for more.

Third – Recalibrate the economics.

For Local and National Government this is one area of public funding– if done right- where we can save money and provide a better outcome to the vulnerable in our cities. The crisis is now so significant and the economics so broken that when we look at the real demands the challenge around traditional viability are becoming less relevant – the cost of not building is now too expensive. For years, successive reports have demanded of government new investment – most recently to the tune of £10billion a year to build 90,000 social rent homes a year for 10 years. However, in the immediate term National Government is unlikely to release this, and Local Government has limited borrowing capacity. We are now exploring instead the opportunity to release capital investment into social housing through partnerships with pension funding. This is long term, low yield, socially responsible investment capital where public land can be leased for the longer term to release capital to be invested into social housing at scale.

An ecosystem solution

What we end up with is an ecosystem solution. A new supply chain of homes utilising an existing supply of underutilised brownfield land based around a different economic model partnership with long term capital investment to rebuild genuinely affordable social housing as critical social infrastructure.

Collective leadership

I know that many of us desire to see change. It is my experience that most people working in the housing industry go into housing because they see this role as valuable and important for society. But the human politics of this is tricky and challenging and we need to create a sense of shared vison and collective leadership – this is why all of us are critical if things are going to change.

Each of us is significant to fixing this problem. Whether you’re having a good housing crisis or on the sharp end, ultimately we get the society and government we stand for. There is no solution to this crisis without collective responsibility to back a long term strategy built on compassion and wisdom.

At the heart of housing is planning and at the heart of planning is a brutal interplay of politics, narrative and money between those that need homes, those that build homes and those that seek to protect the value of their existing homes.

We all too easily absolve ourselves of our collective responsibility with a heady mix of self-interest and complex technicality served with a side of existential climate crisis threat and a chaser of twitter anger.

But together we can engage and advocate for change. Local Authorities can lead a way forward, but we are the wider politics, so let’s get past the headlines and advocate for the essential change needed.